Officers' Lyceums:

Professional Military Education in the Nineteenth-century

Program Overview

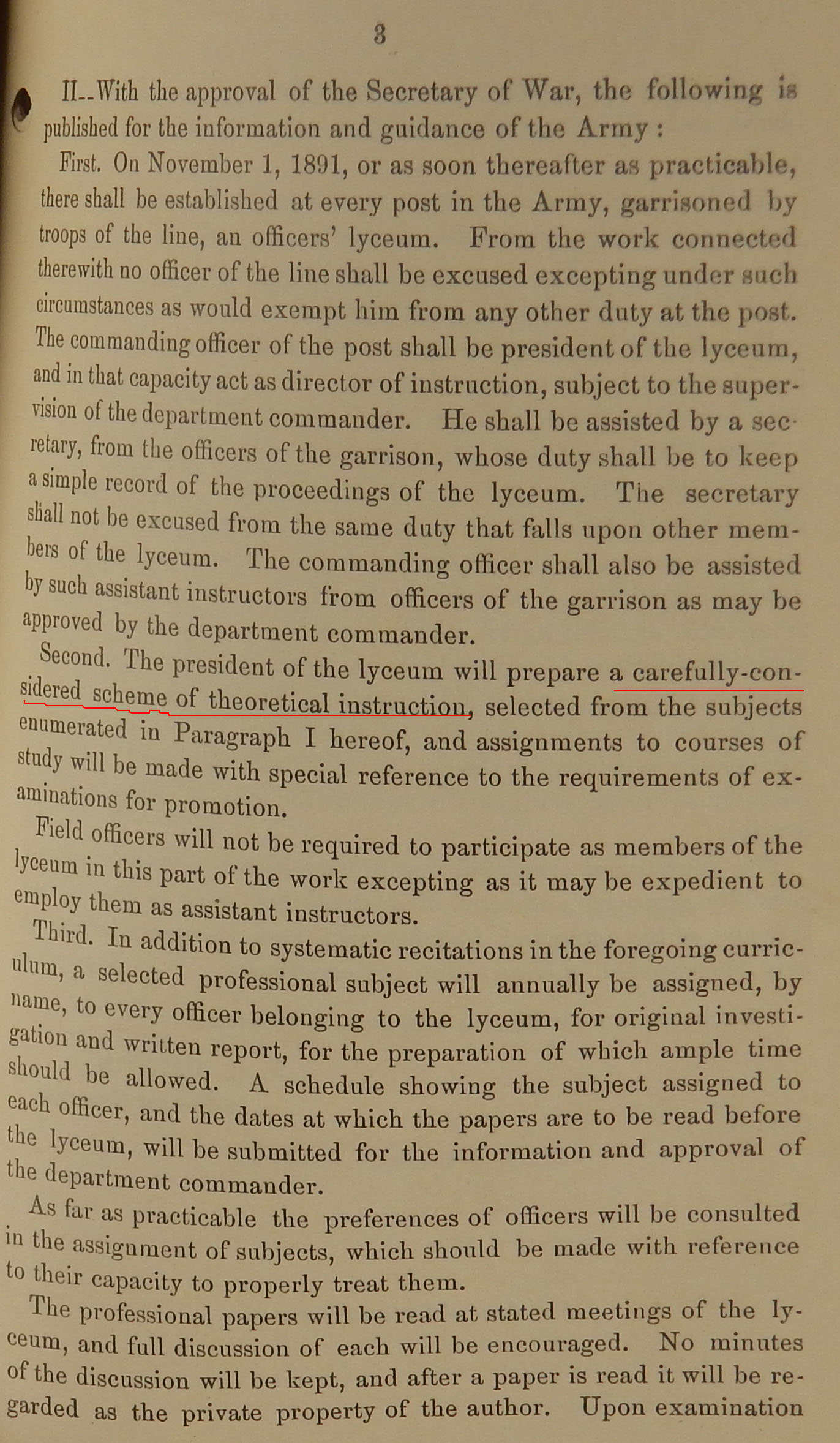

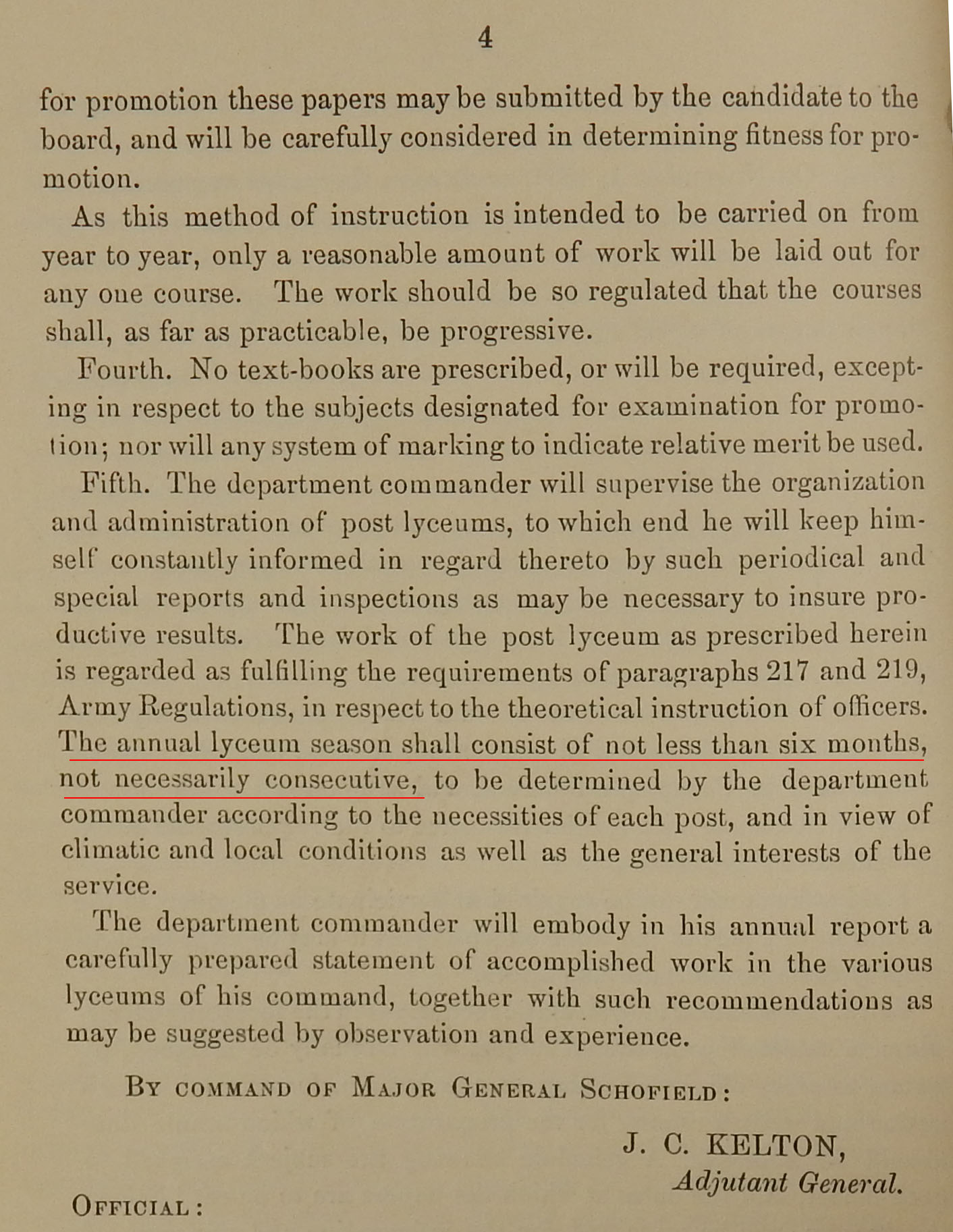

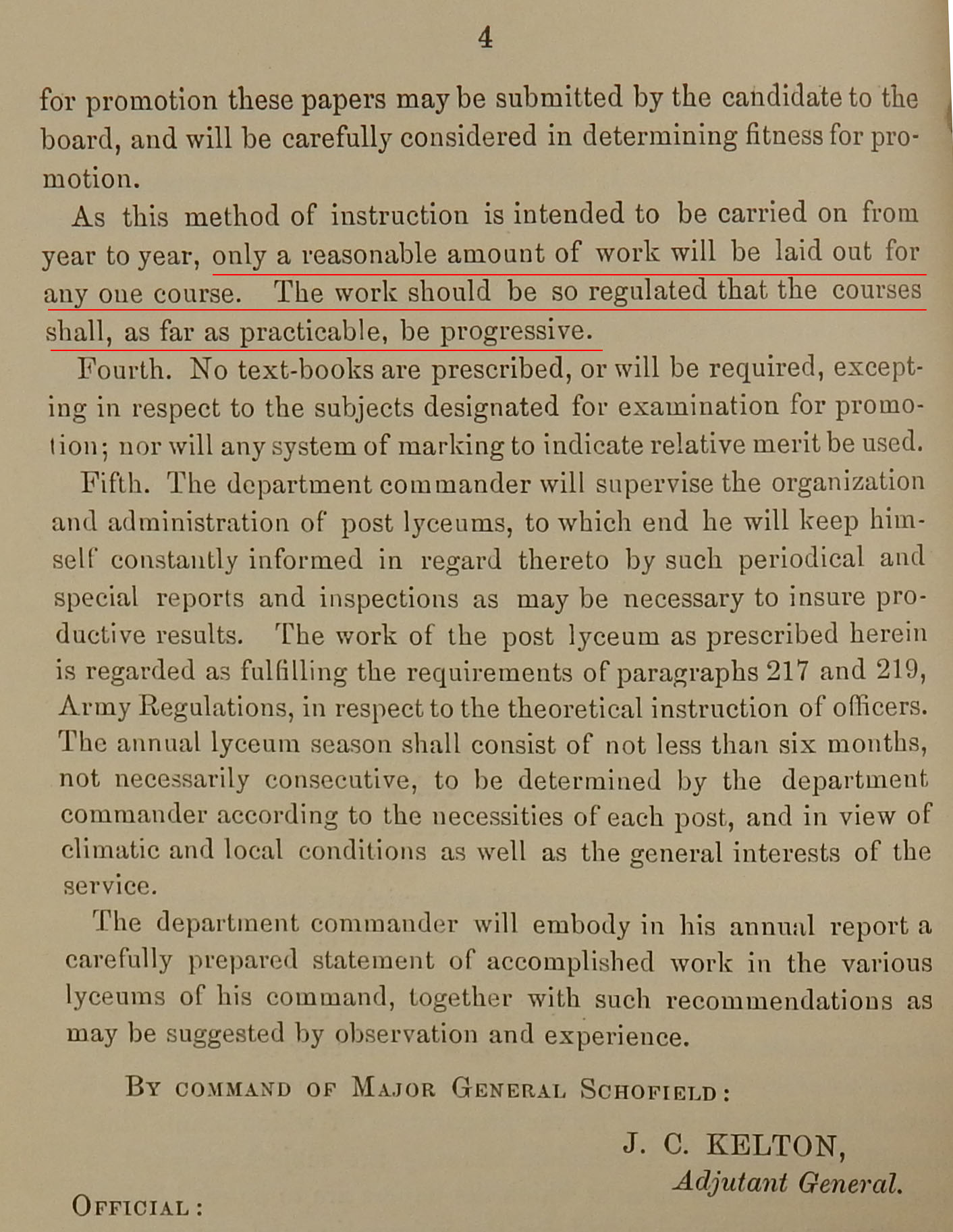

The Lyceum program extended officer education to every post in the Army and provided a venue for every line officer in the Army to further his professional studies on a continuous basis. General Order #80, which established the program in 1891, called for a Lyceum season that covered at least six months of the year, although not required to be consecutive and local commanders were allowed the freedom to organize the Lyceum’s meetings around the other duty requirements of the post. In practice, most Lyceums meetings were concentrated in the winter months when outdoor training was limited.[1]General Order #80, October 5th, 1891, Record Group 94: Records of the Adjutant General's Office, National Archives, Washington, D.C. Each Lyceum was headed by the post commanding officer, who was responsible both for developing the curriculum as well as overseeing all meetings and reporting progress to the Department Commander, usually a general officer. Instruction, as originally organized, consisted of recitations on assigned topics as well as the preparation of original essays on professional subjects, which were then presented to the entire Lyceum and discussed by the other officers. As the Lyceum was envisioned as an enduring program, General Order #80 stated that “only a reasonable amount of work will be laid out for any one course. The work should be so regulated that the course shall, as far as practicable, be progressive” from year to year. The topics of these recitations were drawn from the topics and regulations that provided the material for the promotion examinations, also established for the first time in General Order #80.[2]General Order #80, October 5th, 1891, Record Group 94: Records of the Adjutant General's Office, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Each Lyceum was headed by the post commanding officer, who was responsible both for developing the curriculum as well as overseeing all meetings and reporting progress to the Department Commander, usually a general officer. Instruction, as originally organized, consisted of recitations on assigned topics as well as the preparation of original essays on professional subjects, which were then presented to the entire Lyceum and discussed by the other officers. As the Lyceum was envisioned as an enduring program, General Order #80 stated that “only a reasonable amount of work will be laid out for any one course. The work should be so regulated that the course shall, as far as practicable, be progressive” from year to year. The topics of these recitations were drawn from the topics and regulations that provided the material for the promotion examinations, also established for the first time in General Order #80.[2]General Order #80, October 5th, 1891, Record Group 94: Records of the Adjutant General's Office, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Officers' Lyceum of the 6th U.S. Infantry Regiment, held while encamped at Port Tampa, Florida, in 1898

Intellectual Contribution

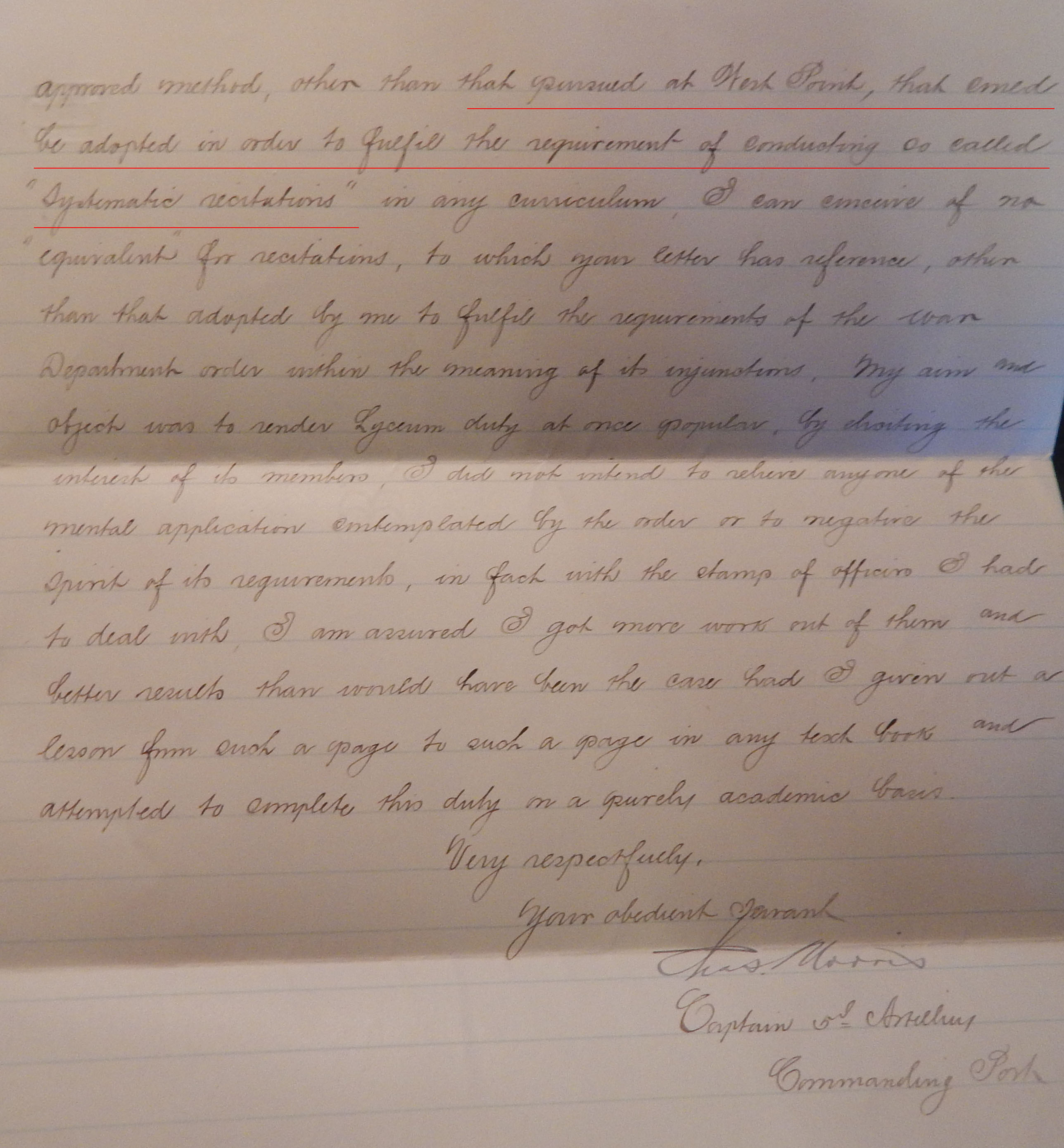

The use of “recitations” was in keeping with the current instructional methods then in use at the Military Academy at West Point, and consisted merely of students presenting to the class, from memory, the word for word memorization of assigned texts.[3]For a description of the recitation system, as implemented at West Point, see James L. Morrison, Jr., The Best School in the World: West Point, the Pre-Civil War Years, 1833-1866, (Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press, 1986), 87-89. The system in place at West Point is also referenced as the model for the Lyceum instruction used at Fort Canby. See Report in reply to letter from department headquarters of January 30th, 1893, relative to instruction of officers in post lyceum, etc., February 6th, 1893, Record Group 393, Entry 732, NARA, Washington, D.C. The original organization of the Lyceums provided somewhat of a mixed bag as far as professional education was concerned. The original organization of the Lyceums, then, provided somewhat of a mixed bag as far as professional education was concerned. Positively, it institutionalized the education of officers at every post in the Army and made it continuous on a year to year basis. The Lyceums were not the first time Army officers had pursued their professional education at the garrison level, as officers frequently met informally to discuss military tactics and other professional topics, but this activity depended on individual initiative and varied greatly post to post. According to historian Carol Reardon, the Lyceums “had done little more than create a formal organizational niche for the discussion groups that had flourished in their unofficial capacity for several decades. But that was no small contribution.[4]Carol A. Reardon, Soldiers and Scholars: The U.S. Army and the Uses of Military History, 1865-1920 (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1990), 15. See also 12-13.

The original organization of the Lyceums provided somewhat of a mixed bag as far as professional education was concerned. The original organization of the Lyceums, then, provided somewhat of a mixed bag as far as professional education was concerned. Positively, it institutionalized the education of officers at every post in the Army and made it continuous on a year to year basis. The Lyceums were not the first time Army officers had pursued their professional education at the garrison level, as officers frequently met informally to discuss military tactics and other professional topics, but this activity depended on individual initiative and varied greatly post to post. According to historian Carol Reardon, the Lyceums “had done little more than create a formal organizational niche for the discussion groups that had flourished in their unofficial capacity for several decades. But that was no small contribution.[4]Carol A. Reardon, Soldiers and Scholars: The U.S. Army and the Uses of Military History, 1865-1920 (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1990), 15. See also 12-13.

Moreover, the preparation of original essays represented a large step in the intellectual rigor of Army education. Yet the reliance on recitation as the primary instructional method, while familiar to the great number of junior officers who had attended West Point, greatly decreased the value, and surely the appeal, of the Lyceums as an educational venue. Finally, the generally vague instructions and wide latitude granted to local commanders by General Order #80 ensured that actual execution varied greatly from location to location.[5]Other than directing a “carefully-considered scheme of theoretical instruction” and making reference to considering the requirements of the promotion exam, General Order #80 left the curriculum and even the frequency and duration of sessions entirely up to the local commanders. General Order #80, October 5th, 1891, Record Group 94, NARA, Washington, D.C.