Officers' Lyceums:

Professional Military Education in the Nineteenth-century

Challenges

The execution of the Lyceum program remained irregular and inconsistent across the Army throughout its existence. While the Lyceums flourished at some posts and a significant portion of Army officer derived some benefit from the program, and through it gained a connection or appreciation for the larger movement for Army reform and professionalization, at other post the Lyceum languished or failed to fully engage officers in useful professional education. The reasons for these irregular achievements had both systemic and local roots.

Shortage of Officers

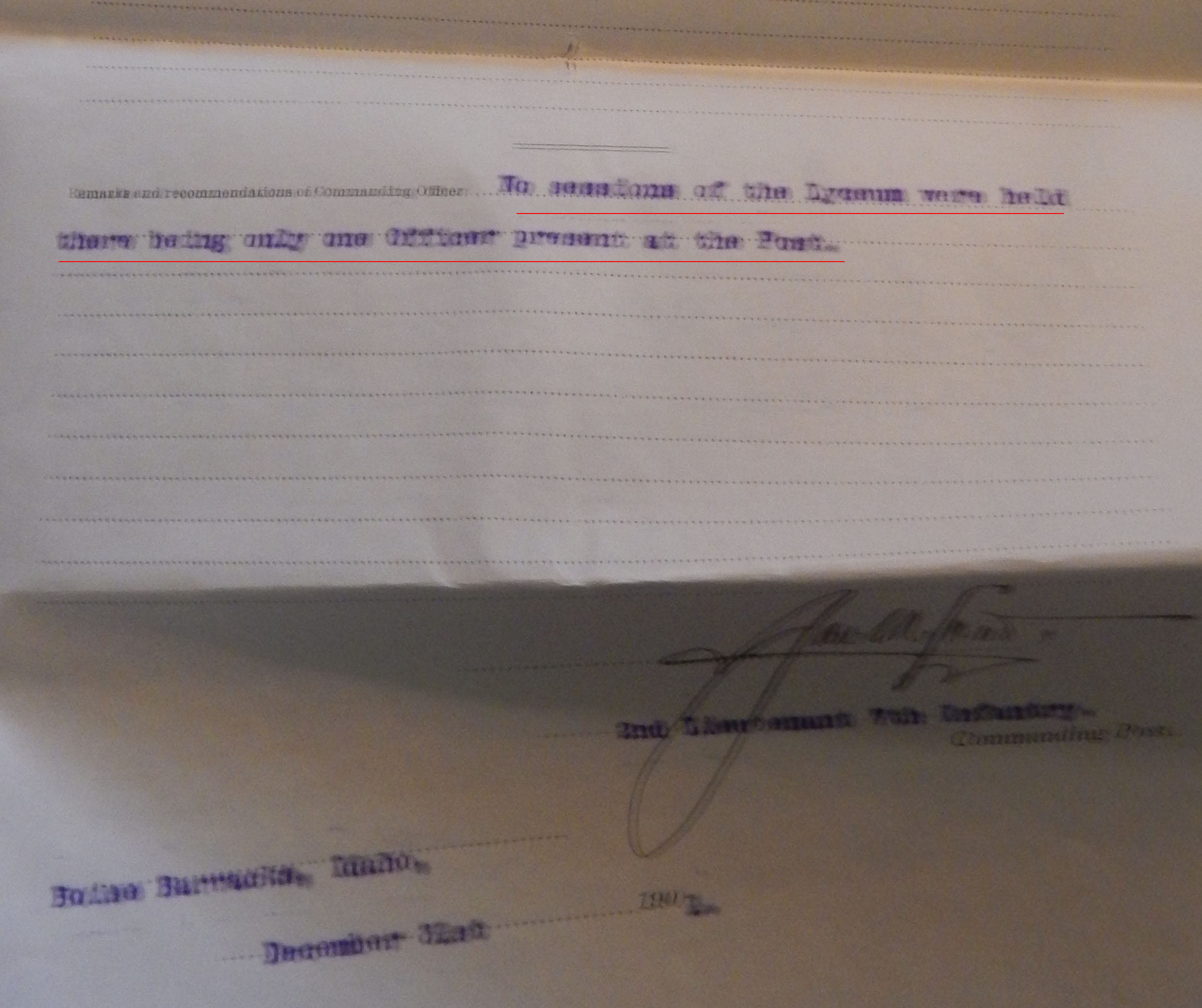

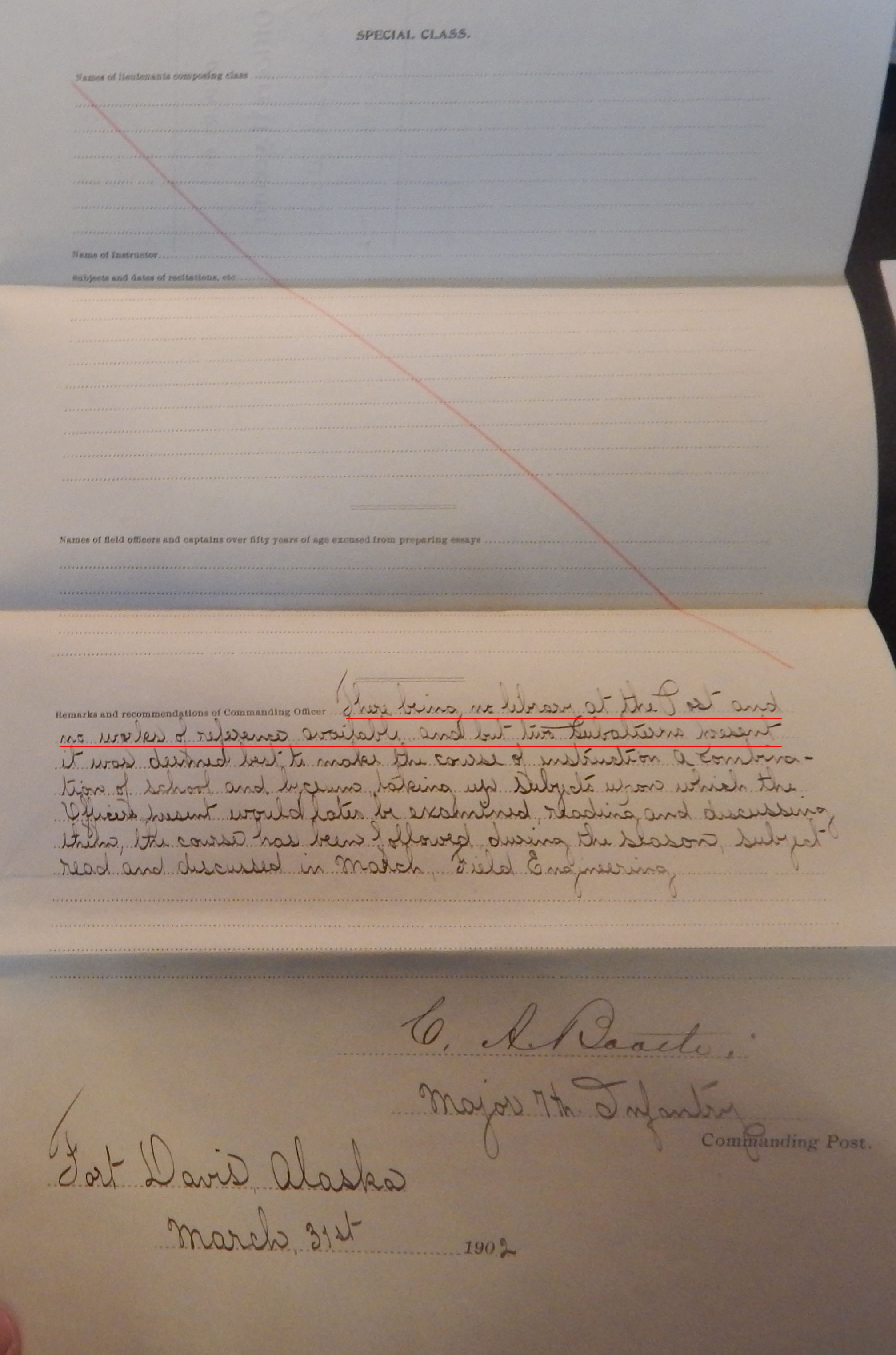

Foremost among the systematic challenges faced by the Lyceum program was the shortage of officers to participate. Some posts had so few officers that achieving the intent of the Lyceum was a practical impossibility. Indeed, in 1901 and 1902 the commanding officer of Boise Barracks, Idaho, Second Lieutenant James M. Loud, reported that “no sessions of the lyceum were held there being only one officer present at the post,” presumably Loud himself.[1]Report of the Officers’ Lyceum at Boise Barracks, Idaho for December 1901, December 31st, 1901, Record Group 393, Entry 732, NARA Washington, D.C. Loud filed the same report for the next three months, subsequent reports were either not submitted or not later lost as they are absent from the National Archives files. Obviously, these smaller posts faced significant, if not insurmountable structural issues in meeting the form and intent of the Lyceum program. Similarly, the commander of Fort Davis, Alaska complained that the Lyceum’s effects were limited because “there being no library at this post, and no works of reference available, and but two subalterns present for duty.”[2]Report of the Officers’ Lyceum at Fort Davis, Alaska for March 1902, March 31st, 1902, Record Group 393, Entry 732, NARA, Washington, D.C. Like Loud, this commander also repeated his same complaint for the next three months as well.

Obviously, these smaller posts faced significant, if not insurmountable structural issues in meeting the form and intent of the Lyceum program. Similarly, the commander of Fort Davis, Alaska complained that the Lyceum’s effects were limited because “there being no library at this post, and no works of reference available, and but two subalterns present for duty.”[2]Report of the Officers’ Lyceum at Fort Davis, Alaska for March 1902, March 31st, 1902, Record Group 393, Entry 732, NARA, Washington, D.C. Like Loud, this commander also repeated his same complaint for the next three months as well. Obviously, these smaller posts faced significant, if not insurmountable structural issues in meeting the form and intent of the Lyceum program.

Obviously, these smaller posts faced significant, if not insurmountable structural issues in meeting the form and intent of the Lyceum program.

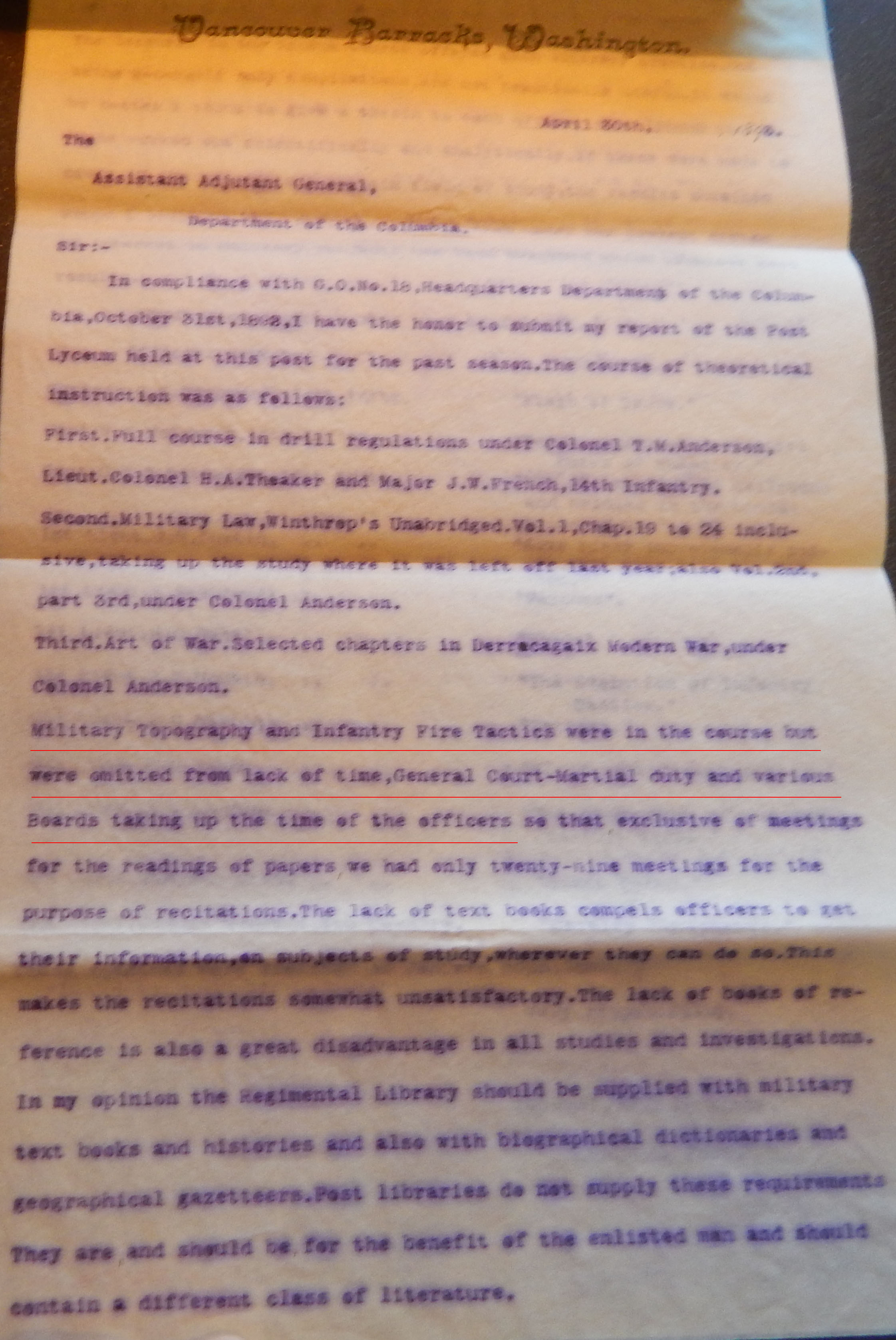

Even posts with a significant population of officers always had the demands of other duties. This issue was frequently mentioned by commanding officers as a factor preventing the Lyceums from achieving their full effect. In April, 1893 the post commander at Vancouver Barracks, which generally had one of the better run and most successful Lyceums, complained in his report to department headquarters that “Military Topography and Infantry Fire tactics were in the course, but were omitted for lack of time, General Court-Martial duty and various boards taking up the time of officers.”[3]Report of Post Lyceum, Vancouver Barracks, April 30th, 1893, Record Group 393, Entry 732, NARA, Washington, D.C.

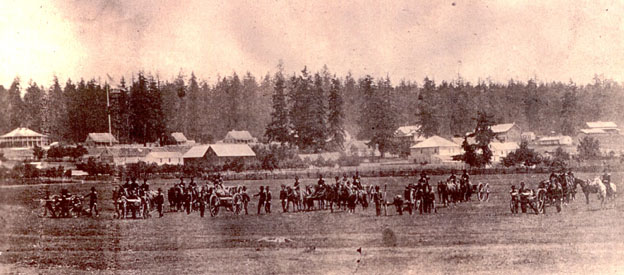

3rd Artillery Trains at Vancouver Barracks

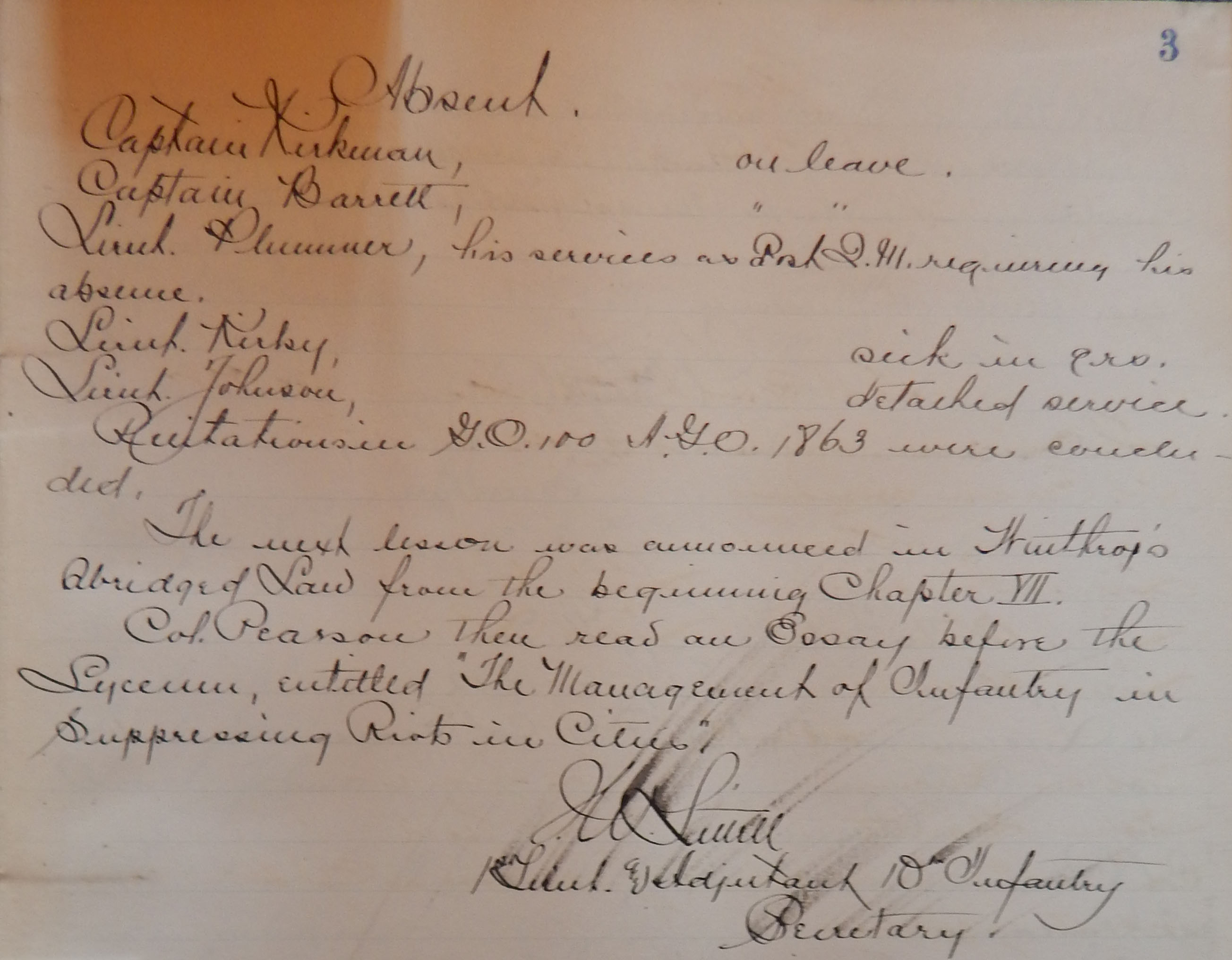

Additionally, even when not specifically listed as a complaint in commanders’ reports, the post logs of individual Lyceums recorded a constant problem of absenteeism amongst officer students, either with or without excuses. The Lyceum at Fort Marcy, New Mexico, for example,

Fort Marcy, New Mexico

Frequently, as described above, Lyceum meetings were canceled altogether when General Court Martials or major events convened, requiring the attendance of a high percentage of officers. Even if the meetings were held, low attendance surely affected the quality of discussion as well as the benefit to individual officers who could only irregularly attend what was designed as a cumulative course of instruction.

Frequently, as described above, Lyceum meetings were canceled altogether when General Court Martials or major events convened, requiring the attendance of a high percentage of officers. Even if the meetings were held, low attendance surely affected the quality of discussion as well as the benefit to individual officers who could only irregularly attend what was designed as a cumulative course of instruction.Text Books

Another common challenge facing the Lyceums was the lack of text books. The General Order founding the program had taken the somewhat contradictory approach of outlining a program of recitations while simultaneously explicitly avoiding the assignment of required texts. This seeming discontinuity was the result of a recognition that a general scarcity of texts that were universally available at the numerous small frontier posts. The General Order left it up to the local commander to decide which texts to use for recitation, or more accurately to determine which texts were available locally. Frequently, as reflected in official correspondence, this meant determining that insufficient, or even no texts were available. As late as 1902, the commanding officer of Fort Davis, Alaska reported that there was “no library at this post, and no works of reference available."[5]Report of Officers’ Lyceum at Fort Davis, Alaska for March 1902, March 31st, 1902, Record Group 393, Entry 732, NARA, Washington, D.C. While perhaps not surprising for a small outpost in Alaska where only two lieutenants were assigned, this complaint was far from an unusual complaint. In 1893, the commanding officer of Vancouver Barracks, a relatively large and well-garrisoned post that also included the department headquarters complained that “the lack of text books compels officers to get their information on subjects wherever they can do so. This makes recitations somewhat unsatisfactory.” He then recommended: “in my opinion the Regimental Library should be supplied with military text books and histories and also biographical dictionaries and geographical gazettes.”[6]Report of Post Lyceum, Vancouver Barracks, WA, April 30th, 1893, Record Group 393, Entry 732, NARA, Washington, D.C.

While perhaps not surprising for a small outpost in Alaska where only two lieutenants were assigned, this complaint was far from an unusual complaint. In 1893, the commanding officer of Vancouver Barracks, a relatively large and well-garrisoned post that also included the department headquarters complained that “the lack of text books compels officers to get their information on subjects wherever they can do so. This makes recitations somewhat unsatisfactory.” He then recommended: “in my opinion the Regimental Library should be supplied with military text books and histories and also biographical dictionaries and geographical gazettes.”[6]Report of Post Lyceum, Vancouver Barracks, WA, April 30th, 1893, Record Group 393, Entry 732, NARA, Washington, D.C.